A looming election certainly can shift the mood. Just six weeks ago, Thomas and I made our way to the Department of Finance to conduct post-budget interviews with Jack Chambers and Paschal Donohoe. The two budgetary ministers, fresh from unwrapping a whopping €10.5 billion package, were in splendid form, happily highlighting the inter-party collegiality that had underpinned the process. Both argued the case for the politics and economics of the centre, and the cruciality of surpluses to social progress.

Last week, however, the budgetary bonhomie between the two ministers, and their respective parties, subsided, replaced by a public spat over the costings in Fianna Fáil’s election manifesto. On Tuesday, just hours after I reported that Fianna Fáil’s electoral promises relied on €500 million in additional tax compliance measures, €2.5 billion in public sector efficiencies and €2.2 billion in “second-round buoyancy effects”, Paschal Donohoe issued a statement saying that the costings left “a lot to be desired”.

The public expenditure and reform minister added that “a close examination of the Fianna Fáil manifesto throws up questions that simply cannot be ignored” and that the costings in the document were best described as “sparse”.

Later that night, Fianna Fáil countered, highlighting the fact that Fine Gael had yet to release its manifesto, and saying that its coalition partner had “deliberately misrepresented” the manifesto. “The budget figures in our manifesto stand up completely,” Fianna Fáil said.

Escalation followed. Chambers, the finance minister, had a tetchy exchange with Fine Gael’s Hildegarde Naughton on the issue that evening, while the justice minister Helen McEntee weighed in, stating that the Fianna Fáil election manifesto was “full of bizarre costings” and “back-of-the-matchbox-style politics”.

Whether that is true is a matter for another day and another column. But the issue around the €5.2 billion certainly caused some rancour, one that points to a rising tetchiness between the two parties.

Tánaiste Micheál Martin addressed it the following day, arguing that the “tone” of the criticism from Fine Gael ministers was surprising. “We might disagree with certain approaches, but this is full-on. It’s the tone and nature of the attacks that has taken me by surprise,” Martin told The Indo Daily podcast. “I do not get the strategy. I think it could be damaging because I think the electorate will be looking at this and people who want to vote central ground parties in will be saying, ‘What? What are they at?’”

He added: “Fine Gael seem to be strategically deciding to target Fianna Fáil more than targeting Sinn Féin. That’s the bit I don’t get and a lot of voters won’t get that either.”

Interestingly, Martin told the podcast that the public will see that the row is “mockeyah”, a Cork slang term I am told reliably told stands for something that is not real or serious.

I am not convinced. Yes, it is commonplace for coalition parties to manufacture conflict and clash during campaigns as a means of highlighting their individuality and their points of difference.

But there is a wider context to these rhetorical clashes between the two main governing parties. It is easy to forget the historic composition of this government, one that brought together the two Civil-War parties together in coalition. It was a marriage of necessity, but it was made possibly by the idea of parity of esteem.

Fianna Fáil brought 38 eats to the table, courtesy of 22.18 per cent of the vote. Fine Gael had 35 and 20.86 per cent. (Sinn Féin, lest we forget, had 24.53 per cent and 27 seats.)

The closeness between the two parties allowed the idea of a rotating Taoiseach. This was a government of equals, with the Green Party firmly viewed as the minority coalition party.

But what happens if that parity of esteem, that electoral closeness, is not there after this election? Would either party be willing to coalesce together if they were the junior partner, and if its leader was confined to the role of Tánaiste for the full duration of its term?

The latest opinion poll from IPOS and The Irish Times shows a six-point difference between Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. Fine Gael was down two to 25 per cent while Fianna Fáil was steady at 19 per cent (Sinn Féin also polled at 19 per cent).

I suspect the gap between the two parties will close between now and polling day. Plus, Fine Gael will struggle to turn its current buoyancy (and that of its leader) into seats due to the sheer volume of longstanding and electorally popular incumbents who are not seeking re-election.

But, if it maintained that trend and turned it into seats, the issue of forming a workable coalition would be delicate.

There is another point here. It was not for nothing that Fine Gael’s attack centred on the economy. The party will struggle to campaign on health or housing (if there is credit there, Fianna Fáil will claim it). However, it will seek to highlight its stewardship of the economy and its role in rehabilitating the public finances from insolvency to prosperity. Calling out Fianna Fáil on the issue brings back attention to the party’s role in the financial crash.

Martin is right. So far, there has been limited interrogation of Sinn Féin’s policies. That will presumably change when it releases its manifesto, and when the campaign debates begin in earnest. So far, the party has been left to its own devices; if anything, the election has taken the attention off the stream of internal crises that beset it in recent months.

This is a short campaign, and it will be a frenetic one.

To date, however, amid the electioneering, the campaigning and the sight of party leaders dancing, there has been limited interrogation of what the arrival of Trump means for Ireland. This should be a dominant issue in this campaign, but, sadly, it has barely surfaced.

As one former political adviser put it to me this week, the only important question during the election campaign is what plans any of them have for the “forthcoming asphyxiation of our economic model by Trump”.

“Manifestos are fiction absent a reckoning with that,” I was told.

It is hard to disagree.

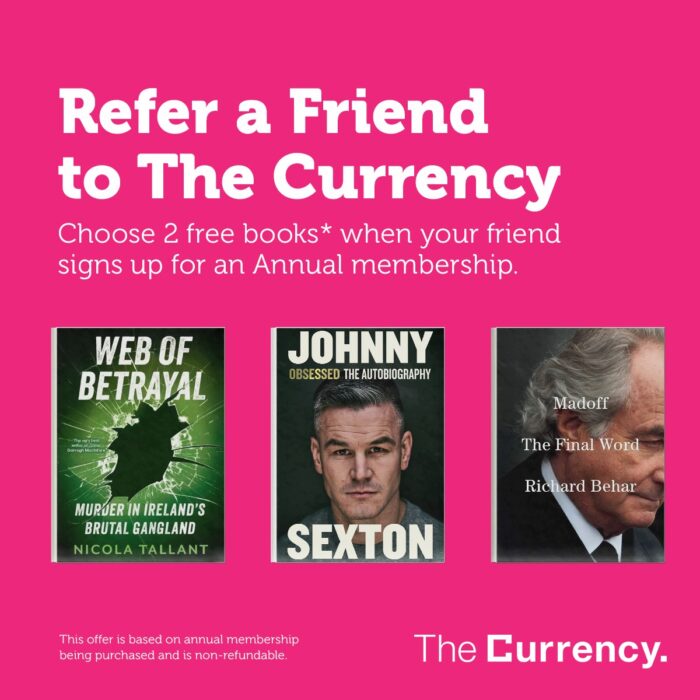

Elsewhere last week, we launched a ‘Refer a Friend’ campaign. When you refer a friend, colleague or family member to The Currency, and they sign up for annual membership, you’ll receive two books of your choice from our selection. It is a fantastic offer, and you can read all the details here. The books on offer are Madoff, The Final Word by Richard Behar, Web of Betrayal by Nicola Tallant, and Obsessed: The Autobiography by Johnny Sexton.

Meanwhile, two of Ireland’s biggest and most successful companies made significant announcements. DCC revealed it was abandoning its conglomerate roots with a plan to sell its healthcare division and review “strategic options” for its technology business. Instead, it will focus on the energy sector. In a major interview, Donal Murphy, its CEO, told Tom why – and how – DCC is going all-in on energy.

Kerry Group has agreed a proposal to sell back its Irish milk processing business to its founding co-op and largest shareholder for €500 million. Years of negotiation surrounding valuation, shareholdings and a simmering conflict on milk price have delivered a deal that makes sense on paper but emotions run high ahead of next month’s shareholder votes, as Thomas explained.

The project director of the offshore wind farm Dublin Array told Alice about bringing her expertise to Ireland's offshore wind sector, how the industry can expand and roadblocks to the nation's 5GW electricity targets. “If you step back and look at where we started, there’s been a lot done in a very short period,” according to Vanessa O’Connell.

There has been a surge in the number of Irish deals involving UK private equity. A&L Goodbody partners Richard Grey and London-based Phil Fogarty told Michael about the trend and argued more is still to come.

Ireland is the only European country offering free water and Uisce Éireann is the only Irish semi-state which has the majority of its staff on the payroll of agencies it cannot control. Something has to give, argued the economist Colm McCarthy.

The Currency has been a long-standing partner of The Entrepreneur Experience. Following this year’s successful event, its co-captain Rena Maycock said it offers that retreat-style distance from the reality and breakneck pace of a start-up, something that is absolutely invaluable.