It’s hard to overstate the importance of working-from-home (WFH). It’s rewiring the world.

Why do we have cities? First and foremost, cities have always been labour markets. People come to cities to find employers and employers come to find workers. The bigger the city, the more employers and workers, the more perfect their matches, the richer the city.

Pushing in the other direction is congestion. Yes, you’re likely to find a better employer in a big city — but so is everyone else. And there’s only so much space within a reasonable commute of the city centre. To be within reach of coveted city jobs, workers have to pay a lot of rent. The same goes for companies.

Cities have gotten bigger over time. Part of the reason for this is that transport technology has gotten better. Better transport reduces commuting time / increases the number of employees and companies within a given commuting time.

This is how cities have always worked. In the 12th century, London was filthy and congested and could only be traversed on foot. That’s where the orphan boy Dick Whittington from Lancashire went to seek his fortune.

The art of running a city is to keep a lid on rents by building ever wider and more densely; while keeping a lid on pestilence with sewers and other services; while growing the effective size of the labour market with buses, trains, metros and motorways.

WFH has come along and messed all this up. WFH means people only have to be in the office three days a week.

Workers initially used WFH to spend less time commuting. Then they realised that they could reconfigure their lives to spend the same overall time commuting, but live in bigger houses.

For the same time spent commuting per week, a worker can live in a mansion in Ballina — spending one or two nights in Dublin — or a three-bed semi-d in Rathfarnam. Many are choosing the mansion.

Companies are making the same decisions as workers. Being the base for work — three days per week at least — companies can’t up sticks and move to Ballina. But they do need less space than they did before.

This week, Meta paid £149 million to back out of a long-term lease in London. The company plans to sublet one of the buildings at its new headquarters in Dublin.

The long-term drop in demand for office space is hard to know. But a drop of about a quarter seems right. Stephen wrote this week about the latest scary trends for Irish commercial vacancies and rents.

The Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom and his team have been collecting data on remote work among US workers. They have found that the number of days spent working from home peaked in the early days of the pandemic at 62 per cent, has fallen gradually since then, and has stabilised at about 30 per cent.

For companies, whose commitments to their office space tend to be long-term, this is a problem to be managed. As companies’ leases elapse, they are rationalising their space and coming up with new arrangements.

For the likes of Meta this is an inconvenience. For the office landlords, it's a crisis.

This year, Gupta, Martinez and Nieuwerburgh had a shot at estimating how the new normal for office workers would shake out for the value of office buildings.

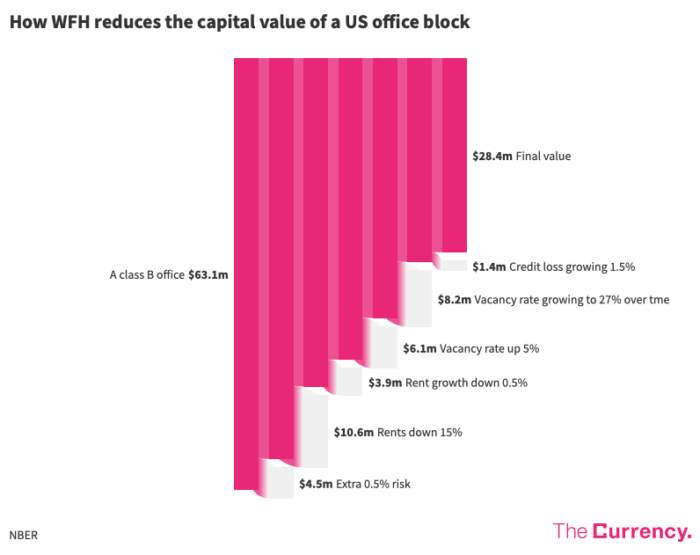

They found a generic class-B office building — that is, a less than brand-new office building — would come to be worth 54 per cent less than prior to the working from home boom.

The following chart shows the steps in their analysis. It starts with a generic, 250,000 square foot class B office building in New York City that’s worth $63 million. First, investors would see it as more risky, and put an extra 0.5 per cent on their discount rate. That would knock $4.5 million off its value. Next, rents have already dropped by 15 per cent per square foot. That reduces the building’s value by a further $10.6 million. Next, the growth in rents is forecast to grow more slowly — by 1.0 per cent rather than 1.5 per cent. This knocks $3.9 million off its value. Next, the vacancy rate has already gone up from 12 per cent pre-pandemic to 17 per cent today. That cuts a further $6.1 million. Next, the vacancy rate is forecast to gradually grow to 27 per cent by 2033. That cuts $8.2 million. And finally, more tenants won’t pay — 3.0 per cent, as opposed to 1.5 per cent previously. That brings the final value of the building to $28.4 million, from its starting value of $63 million.

This is obviously bad news for office landlords. But much more important is what it implies for cities. Cities are losing their raison d’être. I’ll have more on this in the coming weeks.

To be sure, there’s more to city life than good jobs. But jobs matter a lot. A life of rural luxury would tempt many city dwellers. Future Dick Whittingtons need never leave Lancashire.