I’ve been talking at length about how government spending on capital projects goes wrong. With an emphasis on delivery.

What I didn’t ask was whether the projects are worth pursuing in the first place. This isn’t a trivial question. A government could, in a highly efficient manner, waste billions on unnecessary infrastructure.

A government might build something that’s not used very much — the proverbial bridge to nowhere. Or it might gold-plate its investments.

In Ireland, gold-plating is the more common problem. I remember hearing that the fire escapes in the then-new Shannon Airport terminal were fitted out to the same standard as a typical secondary school classroom.

Getting back to my old friend, the Transit Costs Project (TCP), it finds that gold-plating metro lines is a big factor in the 10x cost difference between European countries like Spain and English-speaking countries like the US. The TCP found that over-specified designs increased the cost of New York’s new subway 2.78x relative to typical European projects.

Gold-plated projects and white elephants are a waste, and waste is never good. But Ireland’s growing very fast. Population growth makes over-investment a bit less of a problem. It’s like buying kids’ clothes that are a little loose.

When it comes to project selection, the other problem is underinvestment. A government blowing its capital budget on white elephants and failing to build badly-needed things: that’s underinvestment.

The thing about under-investment is that it’s intangible. No minister will swing because they didn’t build the thing. People can’t point the finger at something that doesn’t exist.

Picking projects

I bow to no one in my love of trains. Trains are a very useful technology for moving people and goods. But rail lines and metros are very expensive. They only work in certain contexts. Rail projects should only go ahead where they make sense.

Rail only makes sense on the very highest-demand routes. It’s worth investing in rail in high-demand areas because one track can move many more people than an equivalent width of road. A metro can move about 40 times more people on a given width of track than an equivalent width of road.

Rail is costly but it moves big numbers. If you’re going to invest in rail, especially in a city, it needs to move big numbers to justify itself.

The other thing about rail is that it doesn’t just serve the existing city. It shapes it. Manhattan or Hong Kong or Tokyo would not be possible without their rail networks. The skyscrapers follow the rail, not the other way around.

Los Angeles is the canonical example of a failed metro system. LA has built out an underground network at great expense, along its most high-demand corridors. And LA is a huge city. The reason LA’s metro has failed is because its metro stations are surrounded by suburban houses with gardens. There’s not the housing density there to justify a high-capacity rail line. So having spent more than a hundred billion dollars building tunnels, the LA metro is half empty.

This could yet be the fate of Metrolink. North Dublin, as it is, doesn’t have the density to justify the cost of a metro. It runs through low-density suburbs and the airport.

But the reason LA’s metro has failed isn’t because few people want to go between downtown LA and Santa Monica. It failed because LA has laws forbidding the construction of apartments along the metro lines. If it were legal to build tall buildings in LA, it’s safe to say its metro would be a success. It would be the backbone of the city, as it is in almost every other big city with a metro.

If Dublin builds Metrolink, there are good reasons to suspect it’ll cost close to $1 billion per kilometre. It’ll be the biggest capital investment in the state’s recent history. Maybe the biggest, in relative terms, since the Ardnacrusha dam?

There’s a world where Metrolink is the ultimate white elephant, only using a fraction of its capacity. That’s its fate unless we build lots of homes along the line. Tens of thousands of them. The capacity of North Dublin will need to grow in line with the capacity of its new transport system.

If — big if — we change the rules to make it possible to build thousands of homes along the Metrolink, the economics of the project flip upside down. If we build the homes, the benefits of the project swamp its costs. Even if we end up spending €15 billion on it. That’s because building rail capacity unlocks enormous land value. The addition of rail enables the building of tens of thousands of homes.

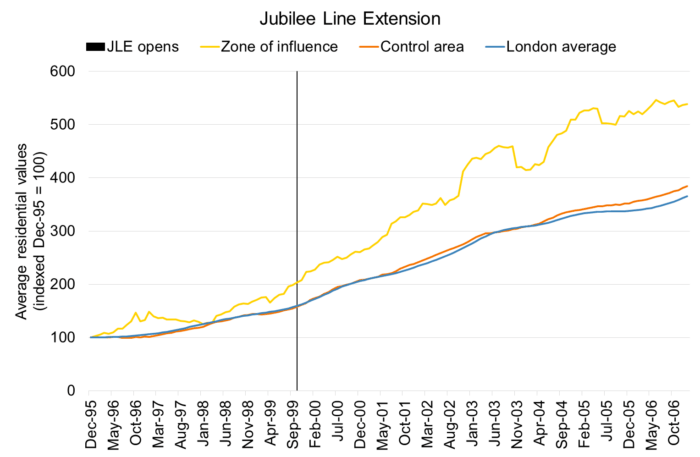

The following chart from Savills shows how the extension of the London Jubilee line impacted property values along the line. The line extension cost £3.5 billion, and it’s been estimated it increased residential land values by £9 billion. The impact on commercial land values hasn’t been estimated. And this is in London, a city not known for its liberal planning rules.

Going back to project selection, the big unbuilt project in Ireland is the Dart Underground. Dart Underground was a proposed tunnel linking Heuston with Connolly. Dart Underground had big potential because it would have allowed the freight lines to the west of the city to be turned into high-capacity commuter rail lines, à la Metrolink. Those lines have the potential to move hundreds of thousands of people. The tunnel would have massively increased the value and capacity of the existing Dart network, by linking it with the centre of the city. The rail system would suddenly be able to move huge numbers. Which would allow the city to get bigger and cheaper.

The Dart Underground is a solution that’s been applied all over Europe, where you have old freight lines running from the periphery to the edge of the city. By linking the peripheral rail terminals with a tunnel, you can a) serve the centre of the city, b) move trains forward and back from across the city without turning them around, which allows much higher capacity and c) increase the value of the whole network by connecting more points in the city. It lets people commute from Bray to Heuston.

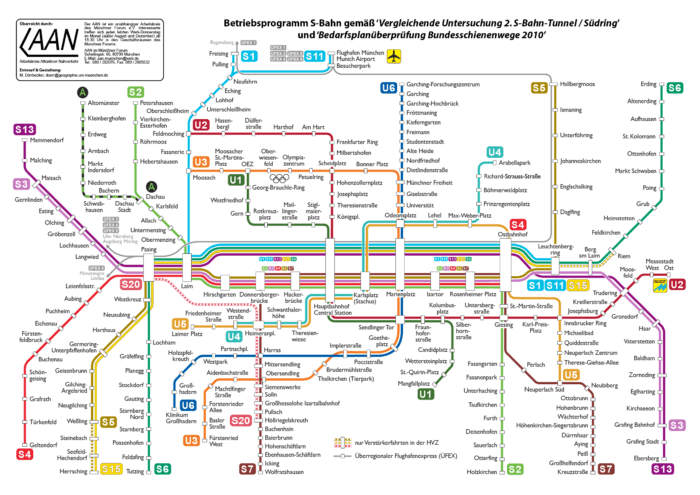

The following chart shows Munich’s commuter rail system. Note the two thick trunks that run horizontally through the middle. Those are tunnels. They link the city’s western terminus with its eastern one. They are Munich’s equivalent of Dart Underground. The first one was converted into a commuter rail line for the 1972 Olympics. The tunnels turned Munich’s rail system into a giant integrated whole. And they enabled much more capacity on each line.

The current plan for Dublin is for much less Greenfield development on the edge of town. That’s enshrined in official plans. Yet people keep moving to the city. Unless we relax the plans and start building sprawling car-dependent suburbs, making bold up-front investments in commuter rail is the only game in town.

Once those megaprojects are in train, we can solve the trifling problem of changing planning law to allow development along the route.

*****

What about the all-Ireland rail review? I haven’t delved into the detailed cost-benefit analysis. But it smells fishy. Rail is great for high-demand lines. For everything else, it’s much too costly. The all-Ireland rail review plan links the regional towns of Ireland. Why do this? For commuters, cars and buses are much, much cheaper. For more on this topic, read Colm McCarthy’s recent column.