One theme of this column is that the appropriate people to control a company are its shareholders — and not its managers, creditors, workers or regulators. ESG investors would have it that companies should be run in the interests of a broad group of stakeholders. I think that’s wrong.

Another theme is that monetary policy is to a surprising extent not about interest rates or money, but about vibes. People’s mindset matters as much as the amount of money in their bank accounts.

Both of these ideas are coming together now in Japan in a surprising way. As a result, the Japanese market — which has languished for 34 years — is turning. In dollar terms, it has returned 12 per cent in the last year, compared to a negative five per cent for the S&P500. That’s not how the Japanese stock market usually works.

The rut

If you were around Ireland for the aftermath of the Celtic Tiger you have an idea of how it felt to be Japanese in 1989. 1989 Japan was the mother and father of a crash, encompassing stocks and property. At its peak, the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was notionally worth more than all the real estate in the state of California. By 1990, the stock market had crashed 60 per cent. It has yet to fully recover.

The economy was in a deep recession. And debt was everywhere. It was in the banks, which were close to insolvency. It was in the companies that expanded too quickly. And it was in households, many of whose houses were worth less than the mortgages held against them.

People did the sensible thing: they put money aside. Households hoarded cash and saved money. Banks stopped lending. Companies stopped investing. Those in work were glad to have a job.

This will all be familiar to anyone who was in Ireland in 2012. The strange thing about Japan, though, is what happened next. Whereas in Ireland things gradually got back to normal; in Japan, everything just got stuck. Households were hoarding money so business was slow. Businesses couldn’t pay their debts. Even at zero per cent interest, nobody wanted to borrow money.

The economy got stuck in a low gear that it couldn’t get out of. It has stayed stuck for the last 30-plus years. Instead of the gradual inflation we’re used to, Japan has had either deflation or very low inflation since 1990.

Japan’s economy got stuck because of a meme: the economy was weak and therefore it was a bad idea to borrow or spend money. This idea got entrenched and infected Japanese society. The longer it went on, the harder it was to shift.

One way it manifests is in wage negotiations. Whereas in previous decades Japanese unions had been fairly militant, in the deflation period they lost their nerve. In the 1990s, unions agreed to no pay increases in return for job security. Since then, they’ve been timid. For more than a decade, the Governor of Japan’s central bank has been exhorting unions to demand bigger wage increases. But the unions have typically sought no more than one per cent per year.

It’s tough for Japan’s central bank because, if workers don’t agitate for higher wages, it’s literally impossible for the Japanese economy to get back to high gear.

Another way the meme has infected Japan is its corporate culture. To be sure, Japanese corporations have never been shareholder focused, like those in the West. Japanese companies have been controlled by their managers, in the interests of their managers, with shareholders an afterthought.

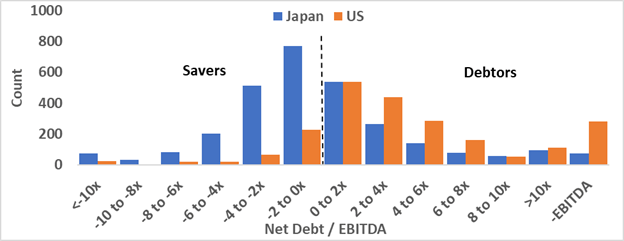

The stagnant economy interacted with Japan’s unaccountable corporate culture to produce something uniquely bad. You can’t blame Japanese companies for the stagnant economy. But they have added to the problem. Perhaps because they were scarred by their debt problems in the aftermath of the crash in the 1990s, Japanese companies have become incredibly cautious about debt. In fact, on net, Japanese companies are net lenders rather than net borrowers. In other words, they have more cash than they have debt. The following chart from Dan Rasmussen shows the different attitudes to debt from US and Japanese companies.

The problem has gradually gotten worse: in 2004, 23 per cent of Japanese (non-bank) companies had more than 20 per cent of their market value in cash; today that number is close to 40 per cent.

This would never fly in the West. Western companies that hoard cash on their balance sheet, with no clear plan for how to generate a return on it, quickly find themselves under pressure from shareholders to hand it over.

This is good for shareholders because they get money in their pockets. But it’s good for the economy too, because capital is freed up to be recycled into the next thing. Instead of sitting around in a stodgy conglomerate’s bank account, capital is used to fund new companies and projects. That’s been another drag on Japan.

The turn

Now, Japan is ditching both of these bad ideas. That’s been behind the success of the Japanese stock market this year.

When it comes to the economy, there have been many many false dawns. So be cautious. But the global inflation shock is exactly what Japan has been needing all these years. It’s raising headline inflation in Japan, through its impact on commodities and the currency. For all these years Japan has been trying to kick-start the economy by generating more inflation domestically, and the most important first step is to get workers to seek higher wages. There are signs this is happening. This Spring, Japan’s umbrella labour union demanded a five per cent pay increase, which is unheard of. Workers are rejecting the idea that Japan’s economy is doomed to be stagnant.

The other big change, from an investor’s perspective, is a shake-up of the governance of Japanese companies. The Toyko Stock Exchange has formally instructed all listed companies whose price-to-book ratio is less than 1x to raise their multiple above 1x, or risk getting chucked out. Price to book is the ratio of companies’ market cap (their value ascribed by the market) to their book value (their accounting value). Where companies have limited control over the price ascribed to them by the market, they do have control over their book value. A company with piles of cash on its balance sheet can reduce its book value by handing the cash back to shareholders, and in doing so, improve its price-to-book ratio.

Japanese companies are responding. More than half of Japanese companies have increased their dividend in the last year, compared to less than 20 per cent for the US, according to Jan Pstrongski of Samarang Capital. At company AGMs — where investors have traditionally either kept quiet or been overruled — more companies are following shareholder orders. At Daiwa, a Japanese investment bank, 49 per cent of shareholder proposals were accepted in 2023 — after none were accepted last year.

Japan missed out on economic growth for the last 30 years. But now that the West is struggling with inflation, Japan is looking much healthier. Over the past year, the MSCI USA index has provided net returns of minus five per cent. The MSCI Japan Hedged index is up by 12 per cent over the same period. Where the rest of the world zigs, Japan zags.